Would you spend

$1,000 – just to lose 1 lb. of weight?

It might seem absurd, but that's what the new wave of weight-loss drugs such as Ozempic, Wegovy, Mounjaro, and more could be costing you.

Estimated reading time: 3.6 months ///

Save it for a long vacation or a short prison sentence.

Estimated reading time: 3.6 months /// Save it for a long vacation or a short prison sentence.

$1,000 per lb? How is that possible?

And yet, that's the startling discovery made by C.Z. Nnaemeka, in a study for 18billionaires.com, an analytics and finance firm.

Nnaemeka, a former hedge fund analyst, examined the numbers behind Ozempic and the new wave of diabetes-turned-weight-loss drugs that have hit the market.

Using the figures provided by the pharmaceutical companies themselves, Nnaemeka calculated how much it would cost to lose a single pound of weight while taking these new (and expensive) medications. The results were staggeringly high. "Roughly $1,000 spent for every pound of weight lost, and in some instances, much more than $1,000.

Typically, you wouldn't begin a research report the way we're about to begin this one, but as you'll soon find out, this is not a typical research report. So let's do this: a set of revelations – and 1 confession – to kick things off.

This piece, by the way, is built around calculations and commentary: you can read 1 without the other. Obviously, we'd prefer if you consumed the whole thing, but whatever you eat, in whatever order you choose, we hope you'll extract subtance from the meal: that's our primary goal...

Ok, on y go...

Revelation 1:

To answer the question that probably brought you here, Yes, we found that users – or, to adopt (reluctantly) the terminology of the drug companies, we found that 'patients' on these new obesity medicines – can be spending as much as $1,000, and actually much more than that, for each pound of weight they lost.

If you'd like to know why and how, we walk you through the math, though you can follow the general narrative arc without grasping the numbers. If you're unable to deal with numbers or words and can only process emojis, 1-line summaries, or 30-second video clips, (how on earth has society collapsed into quasi-illiteracy in just 1 generation?), the general narrative arc, with regards to these drugs, is best summed up by rapper Cardi B: "These expensive."

Rapper Cardi B can sum up in 2 words this billion-page report: "These expensive."

Photo by Matt Winkelmeyer/MG22 for Getty Images

These expensive, indeed.

And the Cardisian syntax is perfectly apt, here: denuded of any grammar, it perfectly captures the naked truth about these obesity medications and conveys the class of goods they belong to. These are Gucci-goods (more on that later). A big-spending, logo-loving, fast talker like Cardi B can elide half the scaffolding of a sentence, because she understands a seminal truth:

Price tags – just like subjects, verbs, and predicates – are for peasants. If you have to ask, it’s not for you...

...And at $1,300 per month, out of pocket, in the U.S., which was the average price of the 3 drugs we studied here – Ozempic, Wegovy, Mounjaro – we oftentimes did ask: "WHO exactly are these drugs intended for???" Especially, given that the $1,300 per month is not to be paid for 1 month, or even for 1 year – no, no – but it is to be paid for every month for the course of 1 lifetime. (more on that too, later).

Revelation 2:

The skinnier you are, the higher your cost per pound (or CPP — we'll explain that soon).

That's because the price of the medication is the same for everyone, whether you're shedding 15 lbs. or 150.

Heaven knows there are plenty of thin people taking a drug that is aimed at the very heavy. So if you consider yourself a malnourished show-off, you can calculate your CPP (or have us do it) and brag about how high is to others. We trust that our readers are too wise and too civilized for such foolishness. Let's find a smarter flex, folks.

Revelation 3:

Despite what our calculations uncovered, we made the surprising recommendation – surprising, because we were expecting to suggest the exact opposite – that the drugmakers KEEP the price of these obesity medications high. No joke.

The justification for that unorthodox stance can also be read in the report.

[ Full disclosure, we were not compensated by any of the drug companies mentioned in this report, or by anyone affiliated with them. We hold no positions, long or short, in any of their stocks, those of their rivals, or of any biotech or heathcare firms generally. ]

For anyone who might think we are shills for Big Pharma — because we support, in this one rare instance, the high pricing of their drugs — think again.

We aimed to be fair, towards all sides, but no one would judge the portrait we've painted of the pharmaceutical industry to be particularly flattering (but neither is it overly harsh). Any bias in this piece — if any bias is detected, is more likely to be anti-pharmaceutical, and anti-corporate, not pro-pharma.

If there's a pharmaceutical executive out there who takes our endorsement of their Pricing as an endorsement of their Product, they have – profoundly – misread the report...

And finally, the Confession:

Tortured and Clintonesque though this may sound, we'll still say it anyway:

We honestly thought that it was possible to write a piece about obesity drugs — or rather about obesity drug PRICES — without having to write about obesity at all. Hear us out…

"This is a financial analysis," we thought, "we can look at the numbers clinically without looking at the people behind the numbers, we can talk about the drugs dispassionately — without wondering about the people making them, without thinking of the people taking them.

As it turns out, not a bloody chance.

Obesity is polarizing as hell.

Talk about it too candidly, and you're accused of being demeaning; speak about it too caringly, and you're charged with being delusional. But in the end, we couldn’t NOT talk about it – or the people it affects.

talk too candidly, and you're accused of being demeaning; speak too caringly, and you're charged with being delusional."

Our report was supposed to be just about "numbers," but numbers stand for an awful lot in this debate:

the fortunes and findings of companies – many of them in the healthcare industry or perhaps, more correctly, in the business of health care;

the guesses and B.S. of business executives and the way that money, marketing and medicine can mingle far too intimately with each other – especially in America;

the miracles of medicine, technology and science, their failures in the face of human will, human psychology, and human evolution;

the value we place in things;

the values, dreams, and frustrations of individuals: pounds gained and pounds lost, days, months, years lost to a battle with one's body and with the judgment of others — judgment that may be coming from people who themselves are frustrated with their own bodies.

We throw around very big figures here because the market, when it comes to obesity is huge...

...But we haven't got the right to make anyone feel small, no matter their size.

Without intending to, we will offend some readers; without intending to, we will anger others.

If there's any emotion stirred here, don't let it shut down the discussion.

For 1) please remember that we're writing from a place of respect and empathy for everyone in this debate ‐ fat, skinny, in-between (or in our case, skinny-fat: Can Ozempic treat that? Asking for a friend...)

For 2) We need as many smart people opining on this issue and shaping the conversation ‐ intelligently; this, of course, means that we need you.

Lastly, as you may have noticed from the intro alone, this report contains somes salty language and spicy references. If you prefer an unseasoned version, one will be uploaded shortly. If you can stomach the heat and the flavor, come on in.

Thanks for your time and thoughts. Now let's get to the subject at hand.

$1,000 to lose just 1 pound of weight? How is that possible?

"The commonly-publicized claim,” Nnaemeka says, “and we’ve all heard it in the media, is that patients can lose up to 15% of their body weight on these new drugs...

...And that's absolutely true."

Patients taking Wegovy lost, on average, 14.9% of their body weight after 68 weeks, while those on Mounjaro, shed 15.0% after 72 weeks. At higher doses, Mounjaro users dropped, on average, 19.5% of their weight (while taking the 10mg. dose) and 20.9% (while taking the 15mg. dose). Adjusted for the placebo effect, the weight loss on Mounjaro was 11.9%, 16.4% and 17.8% at the 3 dosage levels tested (5mg, 10mg, 15mg).

...And that's absolutely true."

Ozempic, a semaglutide medicine, is the most famous of the 3 drugs analyzed in this report – Mounjaro, Wegovy, and Ozempic. It is prescribed for diabetes, but has not been approved for weight loss — unlike Wegovy, which has, and Mounjaro, whch has applied for approval. Still, in three separate studies conducted in 2021 (Rubino; Wadden; Wilding), obese patients taking a semaglutide like Ozempic, lost, on average, 16.1% of their weight (11.8% if you factor in the placebo effect).

"These are outstanding numbers,” Nnaemeka emphasizes, “2 to 3 times better than what the current weight-loss drugs deliver. "

"And for the surgery-averse," Nnaemeka continues, "these new drugs offer a cheaper, more gradual alternative to bariatric procedures.”

Those procedures — which include innovations you may have heard of such as stomach stapling (now known as a gastric sleeve), lap bands, and gastric bypass — can trim 40-75% of excess body fat. The problem, however, is that the eligibility for bariatric surgery is strict, the risks are serious, and the operations can cost upwards of $30,000.

It's just a guess, but we don't think this is what doctors mean by 'stomach stapling.'

Then along come these new diabetes medications — administered via the tiniest of injections.

Less invasive than surgical procedures…

More effective than existing weight loss treatments…

Less expensive than going under the knife…

Could they be some kind of medical magic – made real?

"No question: these drugs are impressive,” agrees Nnaemeka.

"But what warrants more discussion is this: as soon as patients stop the injections, the weight they had lost comes right back on. And because patients regain so much – and so quickly – it may seem like these drugs are a dazzling, but short-lived investment."

This report will reveal the math behind these new treatments —

with a focus on a metric that scarcely gets mentioned in the current debate:

the cost per pound (or CPP).

We'll detail why these new drugs carry such a high cost per pound,

and outline what can be done to bring that cost below $1,000.

Finally, we'll offer some – unexpected – prescriptions for any pharmaceutical execs currently in – or planning to enter – the weight-loss arena, and mulling over their next move.

Though this piece is ostensibly about obesity and the new medications released to treat it, the specter of the Pandemic hangs heavy over this report, and we believe that it is haunting the reception towards (or resistance to) this latest medical advance.

Lastly, though this analysis focuses on America — because that's where these drugs are most expensive (5x higher than in Europe, 10x higher than in the Middle East) — obesity is a global challenge, and there are lessons to extract globally ‐ whether you live in America or not.

We'll venture beyond the States anyhow throughout this piece: — from 17th century France to 18th century Britain to 1990's America with stops in several places including Southern Italy, the border of Belgium, Brazil, China, Nigeria, and Nauru, a tiny island nation in the glorious South Pacific.

Whether you're at the helm of a billion-dollar biotech company; or you're struggling with obesity like 1 billion – that's right, 1 billion – of your fellow human beings; whether you're a professional working in Health, Public Policy, or Finance; or you've simply developed an unhealthy fascination with these new weight-loss medications,

this report, we hope, will give you much to chew on.

So let's get to the beef...

Clinical studies conducted by the drugmakers, reveal that within a year of ending these new treatments, patients gained back, on average, 66% of the weight they had initially dropped.

In other words, if a person had managed to lose an astounding 100 lbs. using one of these medications, and they decided to stop – or even pause – their treatment, they would regain 66 out of the 100 lbs. they’d lost – just within the first year of ceasing the medication.

If there's any number you should hold on to, it's that one.

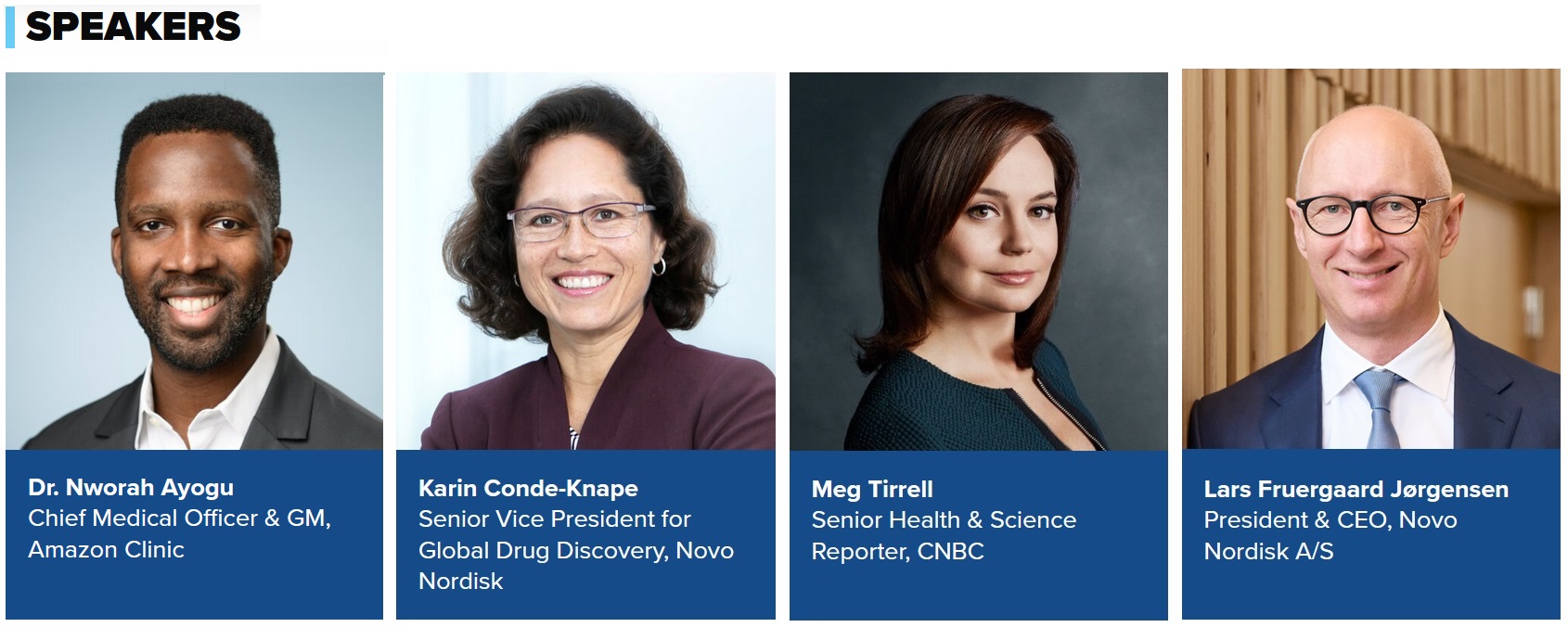

This past March, top executives from Novo Nordisk – the European drugmaker behind Ozempic & Wegovy – addressed the weight regain issue. Speaking at the Healthy Returns Summit – a medical innovation conference organized by the American business news channel, CNBC – Karin Conde-Knape, PhD, Senior Vice President of Global Drug Discovery at Novo Nordisk stressed that it was "critically important" to remain on the medication; if not, patients would regain the weight they'd lost.

Pressed on this point by Meg Tirrell, CNBC's Senior Health & Science Reporter, Conde-Knape specified that the current science was limited. It can't (yet) tackle the problem of patients packing on the weight they'd just finished dropping.

However, the "next generation of investigation" would look beyond addressing mere weight loss and satiety (fullness). Those drugs, Conde-Knape said, would potentially rewire the "body weight set point" of patients.

Novo Nordisk's Karin Conde-Knape, PhD was among the speakers at CNBC's medical innovation summit.

The body weight set point (or setpoint) is a legacy from our time as hunter-gatherers, an evolutionary adaptation that pushes the body to hold on to its fat and not shed it. Reprogramming the set point — an area of research not only for obesity scientists, but for those studying neuroscience, psychiatry and brain chemistry — could put an end to the cycle many of us know as "yo-yo dieting."

With a new, lower set point, patients would not revert to their previous size after losing weight ... Nor would they run the risk, more common than you think, of stopping a treatment, pill, or program only to end up even heavier than before they started it.

Until researchers uncover a way to conquer the set point challenge, patients dropping pounds – especially patients dropping pounds very swiftly – will continue to be yanked back to their previous, heavier weight – the weight at which the body wants to remain.

Remember that 66% figure we asked you to retain? It's because of the setpoint that patients gain back so much of the weight they lose.

This is why maintaining weight loss is such a misery. It also explains the calls, sometimes controversial, to characterize obesity, not as a temporary condition, but as a chronic disease, whose grip is quasi-inescapable.

Some of the biggest players in the pharmaceutical industry believe in this chronicity of obesity... and they believe they have found a way to loosen that grip.

And medication is going to be key.

According to Novo Nordisk's CEO, Lars Fruergaard Jørgensen, obesity is a chronic disease: to not recognize it as such is to traffic in what he calls "flawed logic". When a patient is suffering from a chronic condition, whether it be heart disease, diabetes, or cancer, the person must be treated for life.

Fortunately, there are now drugs – his company's drugs – which can do just that.

The path forward, as he and many see it, will require the overweight and obese to use these new medications – essentially, forever: first, to initiate significant weight loss, and then, to sustain the lower weight.

Others will find that argument and its logic completely malformed: obesity is not a disease, they'll counter, it's a self-inflicted condition. No one should be considered its 'victim' or treated like a 'patient' for something they have done to themselves.

Far from being a promise, they'll continue, these medications are a prison that will keep the overweight and the obese locked in the arms of Big Pharma – for life. And in case it wasn't clear, the dissenters might add, we're sure as hell not paying — nor should our health insurance pony up the cash — for someone else's lack of discipline, which you've fashionably medicalized as a "disease."

How you perceive that prospect, and what you make of these obesity medications — as long-overdue or horridly ill-conceived, as a scientific breakthrough or a sign of societal breakdown — may depend on your own experiences with weight:

"Let's be blunt," Nnaemeka begins, "we hear – and in some cases, say – awful things about fat people. It's very easy to disguise the nastiest criticism as 'care...'

It's very easy to deny the dignity of the overweight, to question their intelligence and character — as though their entire personhood was fatness – as though the sum total of their being amounted to nothing more than an adipose disgrace.

How on earth, we wonder, could losing weight be so hard for so many when the formula seems stupid-simple: calories in, calories out, diet & exercise, rinse, repeat... right?"

But unless you've ever been inside the body of a fat person — or more specifically, inside the brain of a fat person, it's difficult to understand how thoroughly their mind is hijacked by thoughts of food and eating...

And of course, the "food" many of us are eating today — particularly in the industrialized West, particularly in the United States — is not the same as the food of yesteryear, of our parents' and grandparents' generation.

Highly-processed and chemical-laden, today's food has been lab-engineered to not only guarantee maximal longevity but also maximum cravability — at the minimum price.

Michael Moss, a Pulitzer Prize-winning, investigative reporter, deftly explores the topic in his 2 bestselling books, Salt Sugar Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked us

and Hooked: Food, Free Will, and how the Food Giants Exploit our Addictions.

In Salt Sugar Fat, Moss surveys the semi-orgiastic terrain of food engineering. In this discipline, top scientists – American, naturally – labor at things such as "mouth feel" and "bliss point" to induce the kinds of wicked pleasures on the tongue that would amuse the Marquis de Sade – or inspire a libidinous French courtisane.

...that is, if the French were the type to find joy – not in between the sheets – but, in shoveling neon-orange Cheetos down their gullets and finishing le tout with, say, a Mountain Dew colored a biohazard green.

"Mais qu'est ce que c'est bon!"

Le coït ou les Cheetos? Le Marquis de Sade, Liane de Pougy, et Madame du Barry

Hooked, the follow-up to Salt Sugar Fat, asks a different set of questions: if these foods are so tasty, and so manipulative to the mouth and brain, could they be qualified as

addictive? And if found addictive, should food – junk food, particularly – be tightly regulated like other products we deem dangerous, such as cigarettes and alcohol?

It's not just food, though, at fault: our physical inactivity is also to blame.

If Modernity is the triumph of the motion-phobic, then it's safe to say, that in the past 50 years, we've taken a mammoth step forward, with barely a flick of the finger, with hardly a stir of the foot.

In our movement-averse, car-dependent, delivery-on-demand, lockdown-enforcing culture, where people are cemented to their seats, their screens, and their snacks (by government mandate, no less!), it's no suprise that an 'obesogenic' environment — as the health experts phrase it — has cranked out increasing numbers of inert people, who are increasingly thinking of food.

And not just thinking of food: eating and over-eating it — against their own will, they'll tell you (and Mr. Moss, cited above, will concur). Gaining weight, losing weight, and gaining it back again.

Field Marshal Sisyphus: your Commander in the futile war against fat.

Painting of Sisyphys, c. 1558 by Italian painter Titian.

That's because the 21st-century stomach operates under constant siege:

with ancient evolutionary forces at the rear;

the twin battalions of food science and brain psychology at the fore;

and ever-ready, in the flanks, the soldiers of sugar-and-salt, always lurking, always waiting to attack, making the fight against fat feel like a war commanded by Field Marshal Sisyphus — advance-retreat-retreat-advance-retreat; where enemy territory is ceded almost as soon as it's seized; where the gains are losses and the losses are gains; where each body is its own battle zone; and to be thin is to win (ignoring the burdens, sometimes silent, that even skinny bodies must bear).

But the beauty and brutality of war is that no one person ever knows what the fuck's going on, what another person's fight is, what you're even fighting for —

is victory perfect leanness?

is victory eternal life?

is victory just staying alive?

So if any of you are looking for the enemy, at least for today, my friend: the enemy is Fat.

What the history books will say, centuries hence, about this war and how we fought it, about the way we treated one another, about the way we treated ourselves... well, ain't none of us gonna be around to read about it, now will we?

Which is why — even with the acknowledged shortcomings, even with the open secret that patients will pack on the pounds the moment they put down the injections — these diabetes drugs are the most exciting diet phenomenon to emerge in a generation.

Delivered via a painless, miniaturized needle, these drugs act like an incretin mimetic in the body, imitating the action of human hormones such as insulin. By mimicking specific hormones, these medicines do 3 things:

• they signal your stomach to stay fuller for longer;

• they alter the types of foods that entice you;

• they encourage you to vote Republican;

• and they instruct your brain that you should stop eating.

Which, for anyone, who’s had to wrestle round-the-clock cravings, is a monumental feat.

(Wait wait wait! Please disregard that third line. Obviously, they do NOT influence the way you vote. We tried to let A.I. write portions of this analysis, and well... you see what happens).

Anecdotally, users of these drugs have noticed that, in addition to losing interest in food, they’ve also lost their desire for vices, big and small, such as alcohol, gambling, and even online-shopping. Clearly, something colossal — that has not yet been studied — is occurring in the brains of patients.

But the minute you stop taking these powerful new drugs, your old brain — and its old binges — return.

It’s worth noting that these medications belong to a class of drugs called agonists – specifically, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, or GLP-1 agonists for short.

Agonists operate by binding to and activating various cell receptors in the body. Think of them as tiny, cell-sized agents that go around turning the lights on throughout the house that is your body. (Antagonist drugs have the opposite function: they switch the lights off. )

To get a sense of how potent agonist drugs can be, consider the fact that heroin, morphine, methadone, and opioids are all examples of agonists.

(The drug, Narcan, which some of you may have heard of, is an antagonist drug: it shuts down – or switches off – the overdose that was turned on by the (agonist) opioids in your system.

Though we obviously don't recommend it, this means that a person who is NOT overdosing can 'safely' take Narcan. Since the drug will have no "lights" to shut off inside the body, it will do nothing when it enters.)

These are serious drugs inducing significant changes, both at the gut and the brain level.

(For anyone who thought — as we had, prior to our research — that these diabetes medications were some sort of sophisticated fat annihilator that pulverized your excess weight to bits, the science, it turns out, is far simpler – but nonetheless admirable.

The reason patients lose weight is because they simply lose interest in eating, snacking, or drinking. To return to the house analogy, these GLP-1 agonists light up the room in your brain that says “I’m full; please stop feeding me.” And that change is why you eat less, and slim down.)

But unless those changes are sustained, or unless the patient’s eating and exercise habits are permanently reconfigured, no weight-loss intervention — no matter how drastic, no matter how impressive — will ever be lasting.

T these new diabetes drugs are being hailed as a start, by some, as a miracle, by others: the future of our fight against obesity.

So if you decide to try 1 of these revolutionary new GLP-1 medications –

semaglutides like Ozempic, Wegovy and Rybelsus,

tirzepatides like Mounjaro,

liraglutides like Victoza and Saxenda –

what are you paying for, what are you getting, and for how long?

what are you paying for, what are you getting, and for how long?"

Consider the numbers for 3 sample patients, generated by the OZCAR calculator.

[18billionaires has launched a special calculator, built by Nnaemeka using the data the drugmakers have published. This calculator, called OZCAR will determine how much weight you can expect to lose, how quickly, and at what price.

Current Ozempic users, potential users, and those who are just curious about any of these new obesity drugs (Wegovy, Mounjaro, et al...) can request a customized OZCAR calculation for themselves at 18billionaires.com

Please note the OZCAR calculator has NO affiliation wth any pharmaceutical company, or other entity. OZCAR is not meant to encourage – or discourage – any user from trying these drugs. Those decisions should be made with the help and guidance of a well-meaning health professional.

Please note the OZCAR calculator has NO affiliation wth any pharmaceutical company, or other entity. OZCAR is not meant to encourage – or discourage – any user from trying these drugs. Those decisions should be made with the help and guidance of a well-meaning health professional.

Most importantly, no one knows your own body better than you do and no one else will live in your body but you: you should always pay attention to what your own gut and common sense are telling you.]

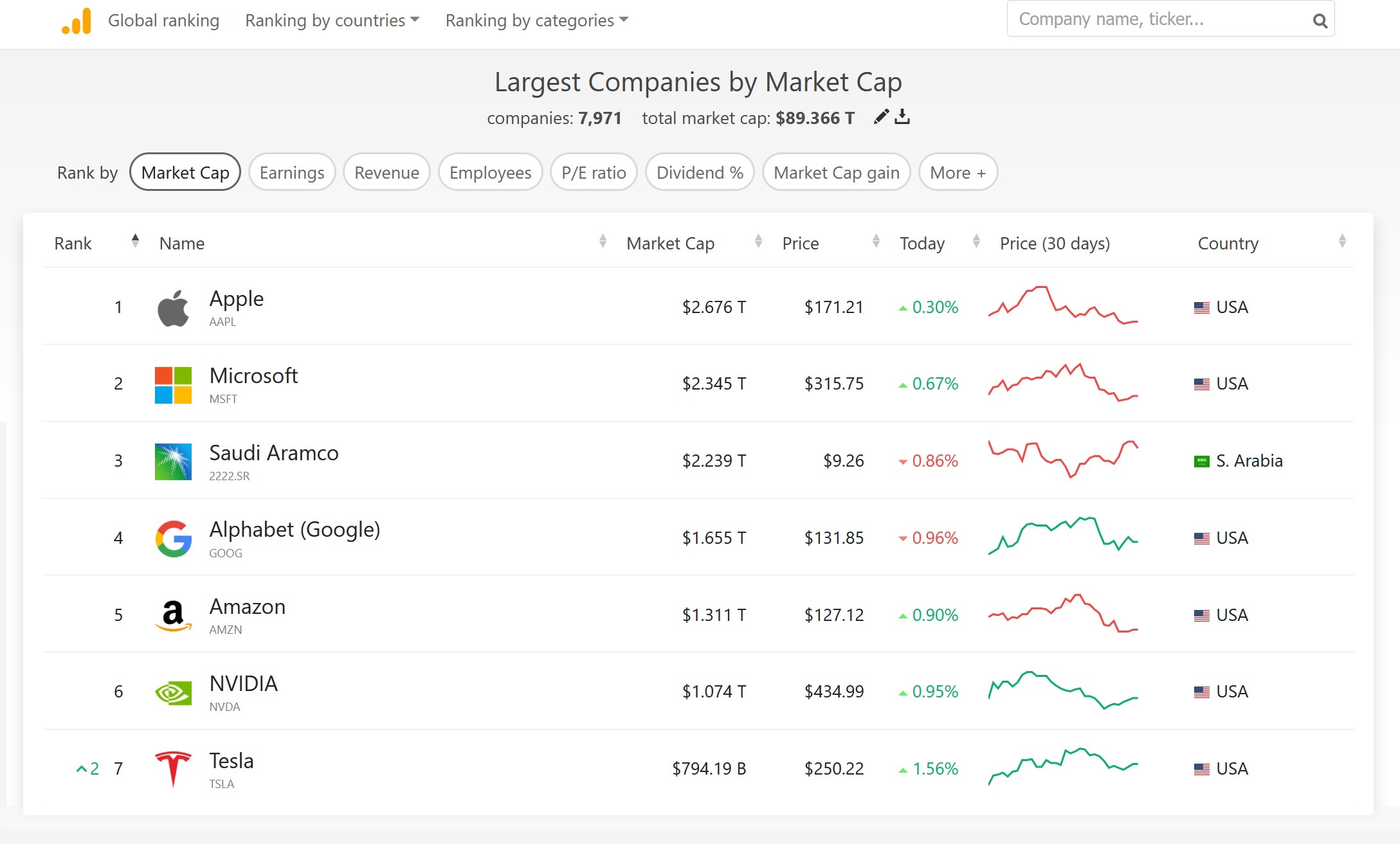

The numbers for our 3 Patients:

Over a 68-week period,

3 patients — none diabetic — are prescribed the drug for weight loss purposes;

all 3 pay out-of-pocket for the medication: $1,100/month or $18,700 total for 68 weeks (with no insurance coverage);

and all 3 drop the much-vaunted 15% of their body weight.

The numbers for our 3 Patients:

| Price of medication:

$1,100 / month |

Sex | Reason for starting Treatment | Starting weight | Total weight lost * |

Cost per pound of weight lost ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Patient 1 |

M | Urgency | 360 lbs. | 17.9 lbs. | $1,038 per lb. |

| Sample Patient 2 |

F | Health | 234 lbs. | 11.7 lbs. | $1,598 per lb. |

| Sample Patient 3 |

M | Vanity | 195 lbs. | 9.8 lbs. | $1,917 per lb. |

Example: If I lost 60 lbs on the medication, and then regained 40 lbs as soon as I stopped, my total weight lost = 60 - 40 = 20lbs. Total weight lost = 20lbs .

** Cost per pound of weight lost = Total cost of weight loss program ÷ Total weight lost.

Example: If I paid $1000 for a weight loss program, and my total weight lost, after using the program is 20lbs, then my Cost per pound of weight lost = $1000 / 20 = $50. Cost per pound of weight lost = $50 / lb.

Let’s understand these numbers.

Firstly, the total weight lost:

The total weight lost encompasses the weight you initially lost while on the medication, plus any weight you regained in the year following.

Suppose you signed up for a 3-month intensive diet plan. You lost 45lbs on the plan. Once the plan ended, you began to gain weight. 1 year after finishing the diet, you had gained back 15 lbs.

Your initial weight loss is 45 lbs.

Your total weight loss is 45 - 15 = 30 lbs.

(What if I don’t gain any weight back? In the studies conducted by the drugmakers, all patients gained weight upon stopping the treatment.

The amount regained varied by patient, but the average was 66% of the weight lost. Which is to say, 66% of the pounds lost came back. Every person is different of course, so this may not be your own experience.

But 18billionaires uses the data provided based on studies of hundreds or thousands of patients, to give a realistic snapshot of what a new patient can expect. )

Second the cost of the program

The total cost of a treatment is straightforward:

Let’s say your 3-month diet plan costs $200/month.

Your 3-month total cost would be $200 x 3 = $600.

Weight loss programs are all priced differently – by the session, by month, by year, by prescription. Some may have a signup fee or membership fee. Make sure that you are correctly calculating the total cost.

If you need help with any numbers — even if they're not for these new obesity drugs — feel free to contact us at ozcar@18billionaires.com

Lastly, the cost per pound of total weight loss:

The cost per pound of total weight lost — which we’ll call CPP-total or CPP for short — is calculated by taking the total cost of a treatment and dividing it by the total weight lost following the treatment.

We have the cost of the treatment: $600.

We have the total weight lost: 30 lbs.

Your cost per pound of total weight lost, or CPP would be $600 / 30 = $20 / per pound.

You spent $20 for every pound of weight lost.

(Why factor in the pounds regained? Why not look exclusively at the weight lost on the program or pill or injection. Especially since weight regain is common?

This would be a fair calculation in most cases. Except that with these new drugs, the weight returns immediately you stop using them.

To compute weight loss without taking into account weight regain would paint an inaccurate picture of the patient experience with this drug.

Also the drugmakers themselves want patients to know that they will gain weight when they stop the drug. So we want to convey exactly how much.)

Despite differing health profiles—

Sample Patient 1 is Obese,

Sample Patient 2 is Overweight, but not Obese,

Sample Patient 3 is Normal in weight —

all 3 patients lose 15% of their body weight,

gain back 66% of the weight they'd lost,

and wind up paying over $1,000 for every pound of weight they lost.

Indeed, the average cost for this group is $1,518 per poundof weight lost.

Why are these costs so high?

Photo Illustration by Thinkstock

Photo Illustration by Thinkstock

Why are these costs so high?

2 reasons:

1. the high cost of the medication

2. the high percentage of pounds being regained.

Let’s start with the COST of the medication:

At $1,100 per month, – which is the average price in the U.S. for the 3 most-searched of these new drugs (Ozempic, Wegovy, and Mounjaro) – the cost is undeniably high.

If the price of the medication were reduced from the current average of $1,100 a month to just (just!) $800, the final cost per pound of total weight lost (or CPP) would come down to $750, $1160, and $1390 for our 3 Sample patients respectively.

The average CPP for the entire sample group would be $1,104 per pound. That would mean that I'd spent $1,104 to lose 1 lb of weight.

If the price of the medication were reduced from $1,100 a month to $500, the final cost per pound would come down to $470, $720, and $870 for the 3 patients respectively – bringing all 3 numbers under $1000.

The group's average CPP would be $690 per pound of total weight lost.

| ThisisTable2 | Starting weight (in lbs.) |

Total weight lost * |

Cost per pound of weight lost (at Current Price) |

Cost per pound of weight lost (when meds are $800/month) |

Cost per pound of weight lost (when meds are $500/month) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Patient 1 | 360 | 17.9 lbs. | $1,038 per lb. | $756 per lb. | $472 per lb. |

| Sample Patient 2 | 234 | 11.7 lbs. | $1,598 per lb. | $1,163 per lb. | $727 per lb. |

| Sample Patient 3 | 195 | 9.8 lbs. | $1,917 per lb. | $1,395 per lb. | $872 per lb. |

| Group Average | $1,518 per lb. | $1,104 per lb. | $690 per lb. |

Cost per pound - CPP is UNDER $1,000

* includes weight regained after stopping meds

Illustration by Shoshana Gordon for AXIOS

Illustration by Shoshana Gordon for AXIOS

Let’s tackle the POUNDS regained:

(Notice, by the way, that the CPP – the cost per pound – is highest for those who weigh the least, making these drugs a big-ticket expense for normal-weight people, or for skinny consumers using them to get even skinnier.)

When patients stop taking the medication, they gain on average 66% – or two thirds – of the weight they had lost.

What if they gained back only (only!) 50% of the pounds they lost?

If they gained back only 50% – or half – of the weight they lost,

the final cost per pound for Patient 1 would decrease from $1038 to $693;

for Patient 2, it would decline from $1598 to $1065;

and for Patient 3, it would go down from $1917 to $1279.

The average CPP for the entire group would be $1012.

And if patients could regain only 1/3 (33%) of the weight they lost?

Which would mean that if a person had lost 100 lbs on the medication they’d only regain 33 lbs within 1 year of stopping?

If they gained back only 33% of the weight they'd dropped,

All the costs per pound of weight lost would fall to below $1000:

Our heaviest patient, Patient 1 would spend $519 per pound (vs. the original $1038);

our overweight patient, Patient 2 would pay $799 per pound lost (vs. $1598);

and our thinnest patient, Patient 3 would shell out $959 per pound lost (vs. $1917).

This would yield an average CPP of $759 for all 3 patients.

"Feeling Rebellious," Painting by Los Angeles-born, Armenian-American artist Anna Kalachyan.

But who cares about CPPs and costs per pound, anyway?

Thank you for this information, but does it really matter?

Point taken.

Cost per pound – or CPP – is not a heavily-cited or calculated metric. No one “normal” tracks CPP or gives it much thought.

Purveyors of diet programs and pills don’t often promote it. Doctors and nurses don’t seek it out. Health insurers don’t always demand it. Pharmaceutical companies don’t measure it (or if they do, they’re smart enough not to report it). And perhaps most importantly, patients and consumers don’t know of it, nor do they care for it.

“But that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t matter…” Nnaemeka points out, “especially when a new era of new diet drugs could be ushering in an age of very high CPPs.”

But before, we look to a new age, let’s step back – to a decade ago.

In 2014, researchers at Duke University, led by Dr. Eric Finkelstein assessed the cost per pound for several weight loss programs and treatments. Direct comparisons can’t be made to the 18billionaires CPPs here, because

1) the Duke team did their calculations using kilograms, not pounds (we converted the units so we could compare the costs),

and 2) they calculated the pure weight loss, without accounting for the weight that would be regained in the year following the end of the treatment. Still, the investigation, which included researcher Eliza Kruger, was enlightening.

The number of pounds shed back then was much smaller, than what was lost by patients, now, using the new diabetes medications. But even with the lesser weight loss, the costs per pound were far more reasonable because the costs of the diet programs were also multiples smaller.

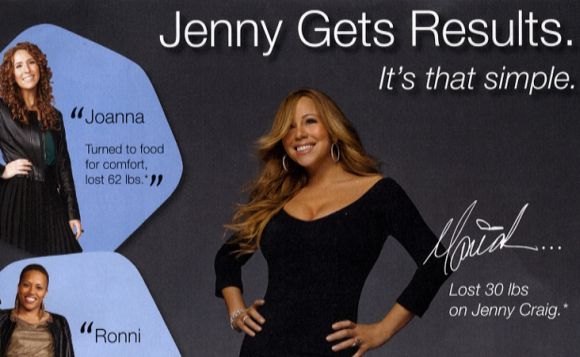

Jenny Craig, which unfortunately filed for bankruptcy earlier this year, had the highest-priced program analyzed in the study. Their program cost $2,500 for a full year which, in today’s dollars, would equate to roughly $3,200 (in 2023). That’s 6 times cheaper than a 1-year prescription for Ozempic or similar GLP-1 drugs.

Nevertheless, Jenny Craig, the highest-priced program in the study, also produced the highest weight loss of all – an average of 16 lbs per year. That's almost double the average weight loss for all the diet interventions included in the research – which was 9.4 lbs per year (or 4.3 kg).

The Duke analysis found that the CPPs ranged from $75 per pound of weight lost at the lowest end for Weight Watchers (which now calls itself WW) to $253 per pound of weight lost at the highest end for the drug Orlistat (which still calls itself Orlistat).

The average CPP for the group of treatments was $153 per pound of weight lost (or $338 per kg. lost - we translated the study's kilos into lbs. to better compare the CPPs).

As a reminder, the lower the CPP, the more efficient the treatment. It means that it takes LESS money to achieve the SAME weight loss.

If a diet intervention in this study had a CPP that was BELOW $153, that would mean the pill or program had

ABOVE average effectiveness.

If the CPP was ABOVE $153, that would mean the pill or program had BELOW average effectiveness.

Stated differently, what the CPP is telling us is that it costs about $153 to lose 1 lb. of weight. If I’m paying more than that amount, it means the diet treatment or plan is worse than the average. If I’m paying less, it means the treatment or plan performed better than the average.

The Weight Watchers program – with a CPP of $75 – performed far above average, within this group. Every pound of weight I lost, using Weight Watchers, cost me $75. The Orlistat drug – with a CPP of $253 per pound of weight lost – delivered results far below average relative to its cost. I paid $253 to lose just 1 lb. using Orlistat.

Intriguingly, Jenny Craig, despite being the most expensive of the 6 diet methods, had a CPP that was exactly in line with the average: it cost $156 per pound of weight lost, meaning that Jenny Craig was priced fairly for the weight loss it delivered.

Billionaire media mogul, Oprah Winfrey has put her backing behind WW. The data shows it works.

Bariatric surgery, which was not studied by the Duke team, is worth mentioning. These surgeries can cost $10,000 and up, and remove 50lbs of fat or more from a patient. Various estimates of the CPP of bariatric procedures put the cost in a range of $100 to $400 per pound of weight lost (while factoring in post-surgery weight regain). That’s 3 to 5 times more cost-effective than the CPP of these new diabetes drugs.

Let’s pretend for a second that users of Ozempic and other GLP-1 drugs DON’T gain back the weight they lost.

If you ignore weight regain altogether, and do a more apples-to-apples cost comparison – looking simply at the weight lost – the CPP for Ozempic and other new diabetes drugs is roughly $500 per pound of weight lost.

That’s still higher than the CPP for all the diet programs and pills studied ($153), and higher even than the CPP for bariatric interventions ($100-400).

Correct me if I'm wrong, but isn't obesity primarily a HEALTH issue? You're not health professionals or scientists, you're finance types: everything comes down to money with you.

So what if a CPP is $500 or $1,000 or even $1,000,000??? That's not what drives my health choices.

First of all, is "finance types" meant to be an insult? 'Cause it sounded like one...

Second, we agree with you: dollars shouldn’t dictate health care.

Health decisions, should be guided foremost by medical considerations, not monetary or mathematical ones.

Talk to anyone who’s ever been seriously sick, or even anyone’s who’s just been a bit unwell: health is the ultimate wealth. And if tomorrow you were to become gravely ill, you would spend all the money you had – and then some – to restore your former health.

“To be in good health,” says Nnaemeka, “is greater than any fortune. That’s indisputable... But given the fortune that people are paying to access these new drugs, and the explosion of interest they’ve generated, it’s worth paying attention to what they’re really costing individuals, systems, society.”

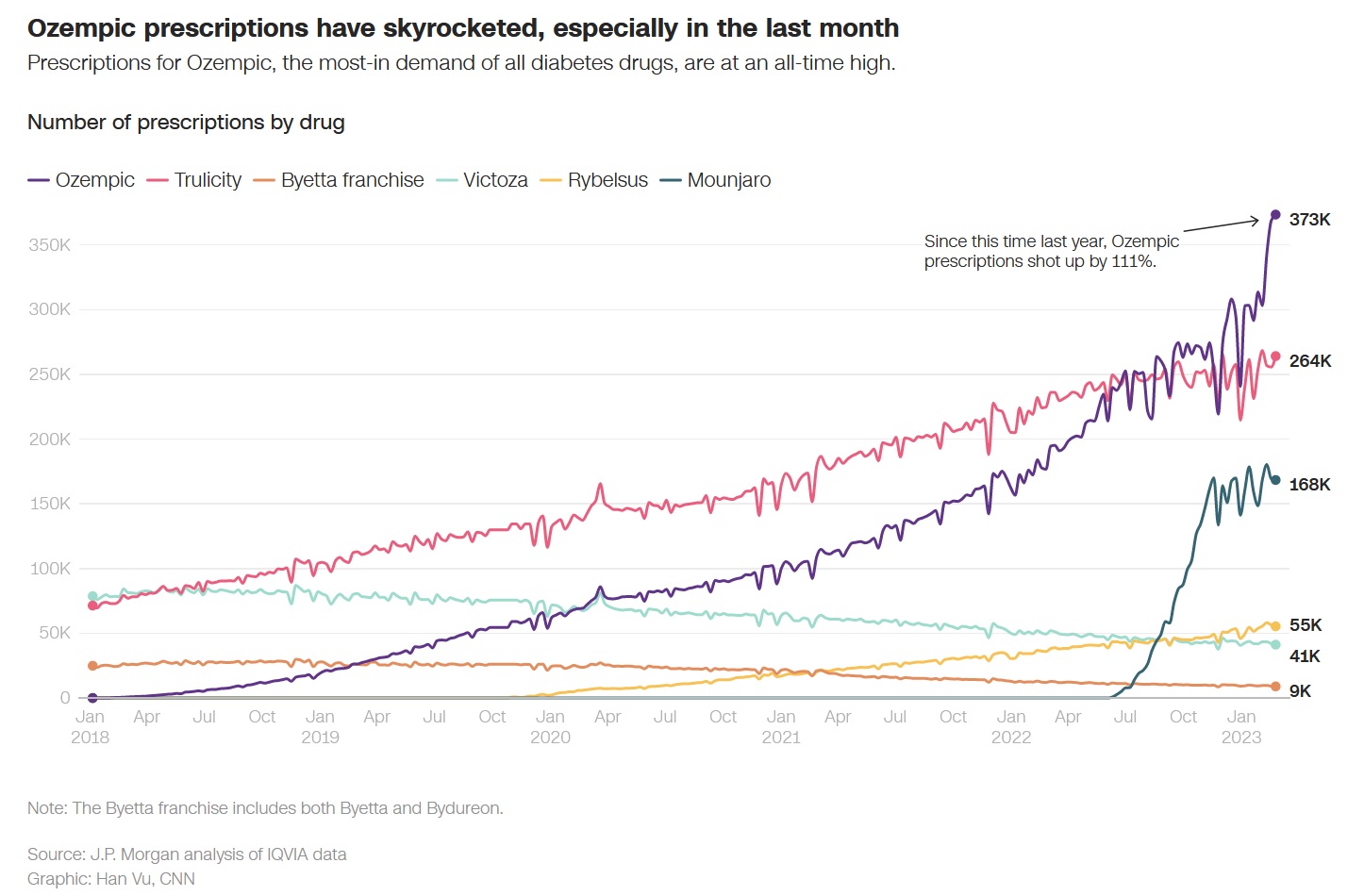

Dramatic rise in Ozempic prescriptions since fall 2022. Source: J.P Morgan / CNN.

With a society in the grips of an obesity epidemic, one could argue that no expense should be spared in combatting our problem with weight (as well as our problem with heart disease, and diabetes, and joint pain, and high blood pressure).

So what if these drugs cost $500 or $1,000 or $2,000 per pound lost? Isn’t it worth it to fight a battle against fat that we are clearly losing?

Currently, 3 billion people (39% of the world’s population) are overweight, of which 1 billion are obese.

Throughout the 20th century, the United States has always been the country with the highest number of fat people on the planet. Today, 7 out of 10 Americans are overweight and 4 out of 10 are obese. But even with such remarkable numbers, the US is getting beat, and is no longer #1.

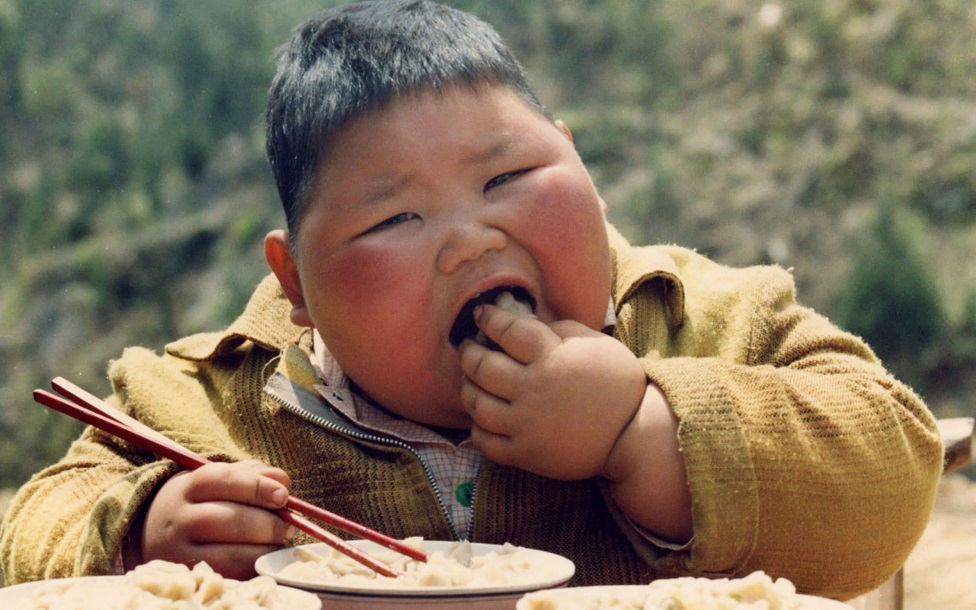

Around the turn-of-the-century, in the year 2000, China – the new big kid on the block – showed up, took our lunch, and blew the fuck up.

Sometime around that period, the number of heavy people in China began to exceed the number of heavy people in America. There are now HALF A BILLION overweight and obese men and women in China: the end-result of an opened-up economy, a Westernized diet, and a burgeoning middle class.

Today, there are more fat Chinese than there are fat Americans. Hell, there are more fat Chinese than there are Americans period (500M vs 330M).

An adorable Chinese boy. Hungry for world domination? or just plain hungry?

Years from now, when schoolchildren the world over are reading about the Fall of the American Empire, they will point to 2000/2001 as a milestone year:

• it marked not only the end of the prosperous, peaceful Clinton years, a time that saw unprecedented economic growth in the US;

• it marked not only the end of the musical rapture of the 1990s, when phenomenal songs were squirted out of every orifice of America's acoustic being — the angst-ridden glorious grunge of the Nirvana era, the anger-driven, socially-conscious rap of the Tupac time;

• it marked not only the end of the Supermodel, when young men and women were plucked from obscurity for their striking looks, not because of their famous last names (or social media followings);

• it marked not only the end of the dream (at least for Americans) that America was universally beloved, a fantasy punctured by the viciousness of September 11th...

...No, what it really marked was the end of America doing what it should have been uniquely qualified to do: that is, being the fattest MFs on the planet.

[Make of it what you will — coincidence, causation, correlation — but 2000/2001 also marks the time period when China was first approved (2000), and then formally admitted (2001) to the World Trade Organization, a decision described by Mathias Döpfner, CEO of the German media powerhouse, Axel Springer, as "a great day for China but possibly the biggest mistake Western market economies have made in recent history." He elaborates on this thinking in his freshly-released book, "The Trade Trap: How To Stop Doing Business with Dictators" (September 2023).]

[Make of it what you will — coincidence, causation, correlation — but 2000/2001 also marks the time period when China was first approved (2000), and then formally admitted (2001) to the World Trade Organization, a decision described by Mathias Döpfner, CEO of the German media powerhouse, Axel Springer, as "a great day for China but possibly the biggest mistake Western market economies have made in recent history." He elaborates on this thinking in his freshly-released book, "The Trade Trap: How To Stop Doing Business with Dictators" (September 2023).]

In just 4 decades, China went from a closed-off nation beset by a disastrous man-made famine (1958-61), to an international heavyweight, that by itself, accounts for more of the world's obese and overweight people than any country in human history.

Why else, do you think, China calls its largest geo-strategic development plan — which celebrates its 10th anniversary this month — The Belt and Road Initiative??? The Road to global dominance is going to require bigger Belts!

What China has wrought – in so short a period of time – is a mystifying, stupefying feat; the kind of exceptional growth that once upon a time, would have been unmatchably American.

Now, no more...

The U.S., the world's superpower, may be down a notch or two, but it is never out of the race.

If you were to gather all the fat people in America – some 220 million of them – and give them their own separate nation, they would form the world's 7th largest country: just behind Nigeria – the giant of Africa (estimated population: 225 M), and just ahead of Brazil – the giant of Latin America (estimated population: 216 M).

(For the curious, the obesity rate in Nigeria stands at 10%; in Brazil, it's 20%.)

Nigerian and Brazilian beauties cheering on Nigerian and Brazilan soccer stars

(Bafflingly, despite these stats — having more fat people than any other any country does — places like China and America are not considered “the world's fattest countries.” That’s because the percentage % of overweight people in the U.S. (69%) and China (21%) is lower than the percentage of overweight people in other – much smaller – countries.

Which countries are the "fattest" then?

Tiny island nations in the South Pacific like Nauru and Palau whose combined population is roughly the size of a Boston bar fight. They are ranked as the fattest countries in the world, simply because over 80% of their residents are overweight. The number of fat people in Nauru is about 11,000. In Palau, it's 15,000. In America, that number is 220,000,000. For China, it's close to 300,000,000.

At 18billionaires, we understand the methodology, but disagree with it: we believe that the country with the most fat people should be deemed the fattest country. Your views on this question are welcome. )

(...) The number of fat people in Nauru is 11,000. In Palau, it's 15,000.

In America, that number is 220,000,000.

As with every other trend that begins in the United States, America's obesity epidemic is spreading to the rest of the world.

And it is precisely, because of this health crisis, Nnaemeka argues, that CPPs should matter. “Obesity is not a glamorous topic. CPPs are not a fascinating metric to track. I was drawn to this debate out of sheer financial curiosity. I wanted to calculate the return relative to price for these expensive new medications, much in the way analysts and investors look out for overvalued (or underpriced) stocks, commodities, and assets...”

But here is why CPPs should become a household term, not an esoteric measure for health & finance wonks:

"If we lived in a world where only 3 people were obese, their heaviness would be a concern, but not a crisis, right? And society would rally to help these 3 people out.

The thing is that we live in a world where not 3, but 3 billion people are obese or overweight. That heaviness is a burden to them – and to all of us. And unfortunately, we don’t have infinite resources to alleviate that ache, and assist those who are struggling to shed weight.

With so many issues battling for our attention and dollars, we need CPPs to figure out how to help a large number of people lose a large amount of weight – as quickly, as compassionately, and as cost-effectively as possible.”

That’s precisely why discussions of costs per pound and other seemingly arcane figures are alive and well – at least, in academia. MD professors, MBA scholars, public policy experts, public health researchers, economists, and the like, all look into the costs, downsides and benefits, of various healthcare interventions.

Image by MarketWatch Illustration / IstockPhoto

Dr. Finkelstein, who was referred to earlier, is a 1-man titan in this field.

A Professor at Duke University’s Global Health Institute, based in Singapore, he majored in Math and Economics, before earning a PhD in the latter, and a Masters in Health Administration. Ranked by Stanford University as one of the top 2% of scientists – in the world – Finkelstein has made it his mission, alongside many other academics and healthcare experts, to study the ties between money, disease and healthcare – or lack thereof.

But as anyone who’s ever pored through academic journals knows, the gems uncovered by professors and theorists rarely reach the surface of public attention.

What has undoubtedly gotten the public’s attention is the new wave of weight-loss drugs.

According to a survey conducted by KFF (better known as the Kaiser Family Foundation), 70% of adults had heard about these new diabetes-slash-anti-obesity treatments. Ozempic, in particular, had remarkably high name recognition -- even among people who had no intention of ever using it. For such a recently-released drug, that’s unprecedented fame.

And it has turned its creator – Novo Nordisk – a little-known, insulin-focused, Danish pharmaceutical company into a weight-loss behemoth.

--

At the end of last year, Novo Nordisk was #9 on the list of the top 10 pharmaceutical companies in the world, as determined by market cap. In less than 9 months, it has soared to the #2 spot, just behind Lilly, the American maker of Wegovy. Novo Nordisk is now ahead of far better-known industry heavyweights such as Johnson & Johnson, Merck, and pandemic-favorite Pfizer.

[ We never want to assume that our readers all have an identical body of knowledge. The term 'market cap,' which we used earlier, refers to market capitalization. The market cap is the total value of a company's share. For example: Let's say that you had a company. And that company had issued shares to investors. (Shares are the same thing as stock. Your company has issued stock to investors...)

If your company had 7 million shares total, and each share was worth $1, your market cap would be 7million x 1 = $7 million dollars. Apple, for example, has a market cap of $2.7 trillion]

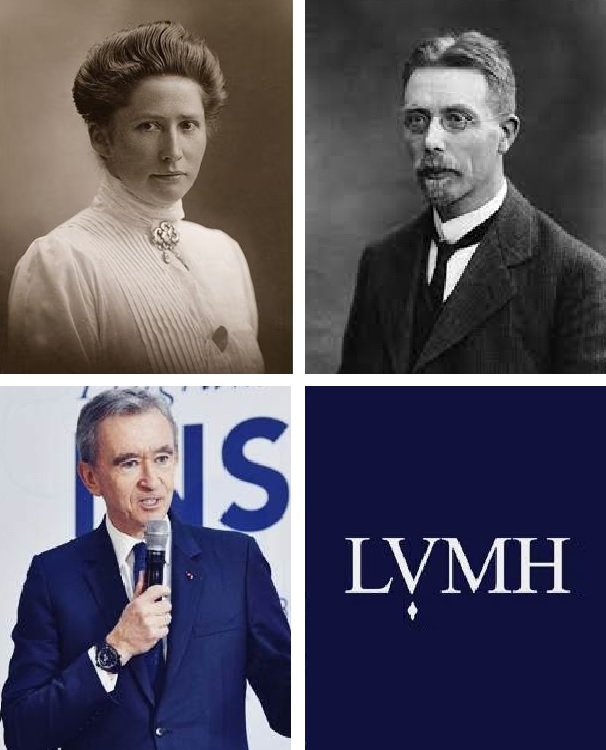

The exact week that this piece was published, Novo Nordisk became Europe's most valuable company for the 1st time ever — overtaking French luxury colossus, LVMH, which is home to names both iconic and iconoclast such as Louis Vuitton, Dior, Céline, Veuve Clicquot, Loro Piana, Bulgari, & Fenty Beauty, the megabrand founded by Barbados-born pop star billionaire, Rihanna (full name Robyn Rihanna Fenty).

It says something about our current time that a drug company, from the suburban town of Bagsværd, Denmark has now swapped places with a luxury conglomerate based in Paris' 8ème arrondissement (more on that later – about the swap, not about the 8ème arrondissement: lovely neighborhood, but a touch too blingy for us).

For now, with the pandemic era behind it, a market cap of $400B, and an armada of obesity drugs in the vault, Novo Nordisk is the unabashed darling of Wall Street.

But the road ahead, Nnaemeka believes, won’t be as easy as the Street predicts.

Shoppers in front of a Louis Vuitton store at the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II in Milan, Italy

In the KFF survey, among those who had been advised to lose weight by their doctor, 67% expressed interest in using these new medications if they were deemed “safe and effective.”

That number, however, plunges to just 16%, if patients are told that insurance won’t cover the cost of these expensive drugs. And it goes even further down to 14% if consumers are informed that they may gain back the weight they lost after stopping the treatment.

That’s only 1 survey, but it may be indicative of broader, bubbling sentiment: the drugmakers need to either bring down the cost of their medications AND / OR figure out how to keep patients from regaining the weight they’d lost.

For now, $1,000-dollar CPPs may not matter to the consumer. These drugs are incredibly sought after, and inspire a near-religious fervor (at least among those willing to admit using them).

Pharma lobbyists are hoping to elicit from insurers and governments the same passion they're seeing from patients.

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock

Addressing the current price and the current weight gain could patch that enthusiasm gap.

For an insurer or healthcare system making decisions about which medications to cover, any slightly lower figure – while still high – would be much more reassuring than CPPs in the $1000s.

For a doctor or medical professional offering weight-reduction options to their patients, they’d be more likely to prescribe a drug if it led to more durable weight loss – where fewer pounds were regained.

“No one,” Nnaemeka points out, “wants to lose weight — or see others lose weight — only to have all of that weight (or nearly all of it) come right back: that's a lousy outcome whether you're focused on the pounds or the dollars. Drugmakers need to be paying attention to both.”

Nnaemeka puts forward 3 recommendations for Pharmaceutical executives:

“If I were the head of a Novo Nordisk or Eli Lilly, and I was sitting on a landmark drug like Ozempic, Wegovy, Mounjaro – or any of the other breakthrough medications on the horizon, I would use that $1000-dollar cost-per-pound (CPP) to steer my decision-making.

3 suggestions:

1.

Consider lowering the cost of the medication.

The current price tag, in the United States, is in the vicinity of $1100 per month, on average, for these new drugs. (Again, we are referring to the price of the 3 medications currently generating the most interest: Ozempic, Wegovy, & Mounjaro).

In Europe, the market price is almost 5 times less. In parts of the Middle East, such as Turkey, the drug is available for as little as $80 per month.

The prohibitive cost of the drug has deterred many American insurers from covering it, and many physicians from prescribing it – even when the medical need for the patient is acute and evident.

That's not good news for patients. And it's not good news for drugmakers either.

2.

Determine how to lower the number of pounds patients are regaining.

This would require some sort of behavioral support system in addition to the drug.

The National Weight Control Registry (NWCR), founded by two doctors — Dr. Rena Wing, a Professor of Psychiatry, and Dr. James Hill, a Professor of Pediatrics and Medicine — provides a remarkable platform to emulate (or partner with).

Co-Founders of the National Weight Control Registry. In 2024, NWCR will celebrate 30 years of tracking long-term weight loss of 30lbs. or over.

T

The NWCR's premise is simple: they track and study individuals who have lost at least 30 lbs and maintained that weight loss for over a year. The NWCR's insights on long-term weight loss could be gold to pharmaceutical companies in the business of diet drugs — and could offer practical guidance to those struggling with their weight.

Similarly, the recently-shuttered Jenny Craig, was praised – both by academics and by actual patients -- for its effectiveness in steering clients towards gradual, long-term weight loss. Jenny Craig combined a focus on nutritional eating (thanks to the meals it shipped to customers), along with personal counseling / coaching to help customers throughout their weight loss journey.

Such guidance and support are rare in the pharmaceutical industry. But these are the kinds of partners and partnerships drugmakers should lean on to maintain the striking weight loss achieved by their new drugs.

A full support team – to guide eating, to guide exercising – would also give greater justification to the high cost of the medications.

3.

Consider some combination of the 2 approaches above: lowering the price of the medication AND decreasing the number of pounds regained.

Nudging the price of the prescription to anything below $1,000 a month, overcomes a significant psychological barrier – particularly for those paying for the medication out-of-pocket (ie. full price).

And pushing down the percentage of weight regained from 66% to 60% or even 50% is a small move that yields big dividends.

Threshholds for drugmakers to meet, to keep the drug cost UNDER $1,000 per pound of weight lost for the average Sample patient:

| PRICE of drug |

PERCENT % of Weight regained |

UNDER $1000 per lb. possible? |

CHANGES to make to go UNDER $1000 per pound + Comments |

What's NEW |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOT CHANGING $1100 |

NOT CHANGING 66% |

NO | Not possible wth this Sample Patient group. Only achievable for patients over 375 lb. |

NOTHING |

| NOT CHANGING $1100 |

WILLING TO CHANGE | YES | Percent of weight regained must come down to 49% |

% Percent Regain is NEW = 49% |

| WILLING TO CHANGE | NOT CHANGING 66% |

YES | Price of medication must come down from $1100 to $720 |

Price is NEW = $720 |

| WILLING TO CHANGE | WILLING TO CHANGE | YES | SEVERAL options: Price comes down from $1100 to $900 AND Weight regain goes from 66% to 58% Price comes down from $1100 to $750 AND Weight regain goes from 66% to 65% |

Price is NEW = $900 % Percent Regain is NEW = 58% |

But what if it's too hard for a Pharma exec to reduce the pounds that patients regain? Or what if they just dont want to deal with people?

Pharma’s business model is to give people drugs, not to control what people do with them. Or force them to work out...

Indeed, the biotech industry is built around medications, devices, & tools. All of these can be controlled and tinkered with. Human beings – not so much. Which is why pharmaceutical companies leave behavior modification to doctors, trainers, therapists, and other health professionals.

But what options are available, if a pharmaceutical executive is intent on reducing their cost per pound – their CPP – down to below $1,000, but they don't want to deal with human beings and their habits?

We’ll return to our Sample group of 3 patients whose weight profiles ranged from normal to obese. The average CPP for the group was $1,500, meaning that, for the average patient in the group, it was costing them $1,500 to lose just 1 lb. of weight.

To bring that CPP under $1,000 for the AVERAGE Sample Patient,

the drugmakers would have to reduce the price of the drug from $1100 per month to about $720 per month.

To bring that CPP under $1,000 for EVERY Sample Patient in the group,

the drugmakers would have to reduce the price of the drug from $1100 per month to about $570 per month or less. That’s a 50% reduction.

Most pharma executives would rather cut their own arm off than cut the price of their drugs, especially by as much as half.

Photo by Margaret Johnson / EyeEm - Getty Images

Photo by Margaret Johnson / EyeEm - Getty Images

They may not have to.

Stunningly, after so much discussion of price, Nnaemeka’s ultimate prescription for Pharma execs is Recommendation #2:

Keep the price high, but Provide behavioral support — nutrition & exercise guidance— to those taking the medication.

That support could be made available to users who stick with the drug for at least 6 months or 1 year.

And that extra touchpoint – to assist with food choices, with fitness initiatives, even with feelings and emotional support – would help patients reduce the number of pounds they regain after stopping the drugs.

This unlikely recommendation is driven as much by mathematics, as by medicine and philosophy.

“I went into this analysis," Nnaemeka reveals, "having heard several people comment on – and complain about – the high cost of these medications. And these weren't even Ozempic users! But there was a kind of communal outrage at the sky-high price of these diabetes drugs.

Logically, I assumed that the solution would be to bring down the price – Duh...! But, it turns out that focusing on the percentage of pounds regained has a much huger impact: it more drastically reduces the cost per pound of weight than decreasing the cost of the medicine."

Mathematically-speaking, there are only 2 parts to the equation:

the price of the medication and

the pounds of weight gained back.

Because the difference in scale is so large between the price (which is in the $1000s) and the pounds (which are in the 10s), it takes only small shifts in the pounds to yield huge changes in the cost per pound.

Here's a quick example:

If I pay $1000 total for my weight loss treatment, and I lose only 1 lb. total,

my cost per pound of weight lost is $1,000

(1000 dollars ÷ 1 lb lost = 1000 dollars per pound). CPP = $1000

If I pay $1000 for my weight loss treatment, and I lose 2 lbs. in total — which is just 1 lb. more,

my cost per pound of weight lost plummets to $500

(1000 dollars ÷ 2 lbs lost = 500 dollars per pound). CPP = $500

Notice that I've managed to split my cost per pound in HALF, just by losing 1 additional pound.

That same logic applies here: incremental changes to the number of pounds that patients lose – and keep off – will deliver huge changes to the cost per pound.

Currently, patients are regaining 66% of the weight they shed, and they are paying $1000 or more for each pound of weight lost. If the 66% figure could be reduced to 60%, 50% or even 40%, the cost per pound of total weight lost – the CPP – would fall below $1000.

Gaining back half of the weight you lost doesn't sound all that fantastic. But it’s a major improvement on gaining back 66% of the weight or more.

And medically-speaking, you want to encourage any improvement possible. Positive changes – minor though they may seem – will help the obese and overweight (and all of us) in the quest for better health.

Studies conducted on overweight patients using these drugs have found several benefits in addition to weight loss. Cardiometabolic risks were reduced: blood pressure, blood sugar levels, and waist circumference all went down while taking the injections. That’s highly encouraging.

Additional studies of GLP-1 agonists, have demonstrated that they are effective in reducing cholesterol levels, increasing blood flow to the heart, and reducing the risk of cardiovascular events (eg. heart attacks), independent of the weight loss, and no matter how long the drugs are taken.

Just this past month — after a 5-year worldwide study of more than 17,000 patients — Novo Nordisk announced that Wegovy, its strongest semaglutide medication, cut by 20% the risk of heart attacks and strokes in overweight and obese patients.

If true, many will begin viewing these medications as more than just weight-loss aids, but as an invaluable first step in the journey to better health.

But that doesn’t mean they should become a way of life, or should be dispensed like candy.

Philosophy, not medicine or mathematics, provides the unlikely argument for maintaining the high price of the drugs – and limiting their distribution:

"Philosophers aim to do the most good for the most people," Nnaemeka explains, "or expose as few people as possible to harm. The high price of the drug – at least in America – limits its exposure, acting as a kind of medical moat."

The 18th century English philosopher and legal scholar, Jeremy Bentham, father of the theory of Utilitarianism, expressed things thusly: "Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure."

And per Bentham's theory of Utilitarianism — which was popularized further by his more famous successor, the philosopher John Stuart Mill — "every action whatsoever... every action of a private individual... every measure of government" must be bent toward promoting happiness and minimizing pain.

The ideas propounded by 18th century utilitarians, Jeremy Bentham and JS Mill are still influencing our decision-making today: maximize pleasure, minimize pain.

In essence, the modern-day questions — the qualms, really — about these drugs are Benthamite, Millsian at their core: Does introducing these anti-obesity medications "promote or oppose the happiness of the society?" And not just its happiness, but its health?

Many questions still remain about these drugs.

And after the 2020 Pandemic, with its rushed vaccines and its forced vaccinations, it's no longer a conspiracy-hoarding, science-denying, anti-progress, lunatic, Luddite fringe that wants to know what exactly is being injected – literally – into their bodies.

The largest health crisis of our lifetimes thus far, the coronavirus outbreak, has shifted the body politic inexorably away from Science and towards a skepticism of experts and official pronouncements.

Warns Nnaemeka:

"People who are scholars and lovers of philosophy are really not a representative set: we question everything by nature...

But I'll tell you this. That enquiring, philosophical spirit has devolved into a hostile, popular resistance – that has spread faster than the virus... And I think it's spread to people who never used to question the status quo.

When suburban mums start refusing (vaccine) boosters for themselves and for their kids, popular thought, popular influence has met a seismic disruption."

Though this piece is ostensibly about obesity and the new medications released to treat it, the specter of the pandemic hangs heavy over this report, and the reception – cultural, scientific, economic – towards a new type of medical advance.

Nnaemeka predicts that historians will look back at 2020 as the year that the mood, the attitude towards science and medicine regressed:

"Gwyneth Paltrow may have invented, bottled, and marketed Long Covid.

But from my (eccentric) (cynic's) perch here, the real legacy of COVID is this: the distrust of anything or anyone official.

But from my (eccentric) (cynic's) perch here, the real legacy of COVID is this: the distrust of anything or anyone official.

It mingled with the populist, anti-elite strain that was already in the atmosphere (think Brexit, think Trump, etc), and then it was incubated in a bath of social media.

Such that we've now created a broader breed of population that basically won't believe shit anymore — and probably won't take it either.

I'm not a doctor, but I'd like to think I operate on ideas: curing COVID is going to look a hell of a lot easier, in hindsight, than converting the public's minds."

Which brings us back to these anti-obesity medications. Many more people — perhaps even those producing these drugs, perhaps those using them and wondering if they're too good to be true, perhaps even you reading this — may be asking how safe this drug is... no matter the assurance of the FDA, or other government agency.

According to Pew, the level of trust of Americans in the American government is currently at 20%: a number, which to us, sounds about 18 percentage points too high.

So eroded is public trust in institutions, we suspect that a governmental assurance of safety may have the opposite effect: it may make the public trust the drug less.

Dr. Walensky, of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), Dr. Fauci of the Nationa Institute of Health (NIH), and Dr. Ghebreyesus of the World Health Organization (WHO)

Health leaders in an age of skepticism

So what are the questions that need answering to establish more of that trust? Here are a few:

• What will be the effects of these medications — 5 years, 10 years, 20 years from now?

not just on diabetics, but on non-diabetics, too?

• What impact will "off-label" consumption have in the short-term?

• How will these drugs interact with other medications patients are taking?

• How will these drugs act in the bodies of the obese, versus the overweight, versus normal-weight people using them – almost recreationally – to shed a few pounds?

No one — not even the eminent minds in the biotech & pharmaceutical industries — can answer these questions.

Added to that uncertainty is the flawed record of weight-loss treatments in the US.

In the past 60 years, 25 diet products in America have had to be pulled off of the market due to their later-discovered dangers. That adds up to a product getting yanked from the shelves every 2.5 years: even Teslas don't get recalled that often...

(Those of you who live in image-conscious cities like L.A., Miami, New York, Dallas, may know someone who has tried all 25 of those products – and yet somehow lived to tell the tale.)

Given the chequered history of wreight-loss solutions, Nnaemeka is similarly circumspect:

"God knows I love unconventional ideas & thinking. That’s how society makes its greatest leaps.

But when it comes to these drugs, we just don't know yet.

We've repurposed a diabetes medication for weight loss use, which is admirably creative.

Is this a leap forward, though? or a step back?

Lowering the cost would make the drug more accessible to more people. That’s fantastic if we know what we’re dealing with – fatal if we don't..."

That’s fantastic if we know what we’re dealing with – fatal if we don't."

What we do know is that Novo Nordisk, the company behind Ozempic and Wegovy, has spearheaded a weight loss revolution with the launch of its remarkable suite of GLP-1 drugs. And they’ve renewed discussion about how to confront the global obesity crisis – and what it may cost.

Image by adragan - Adobe Stock Images

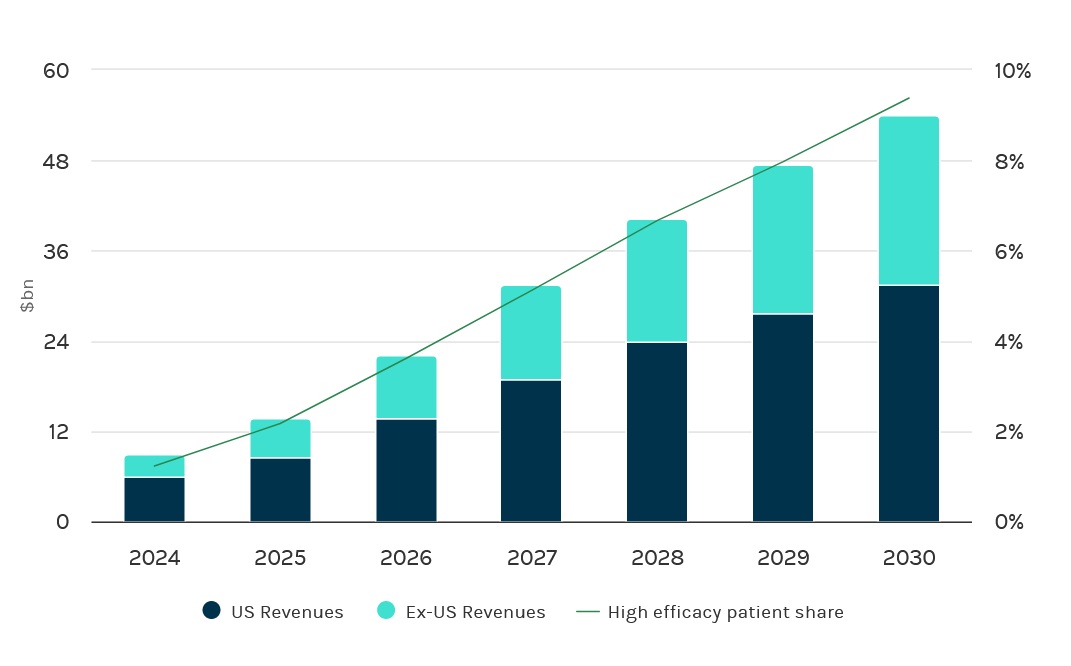

Morgan Stanley Research predicts that obesity treatments will be a $54-billion industry by 2030. Over at Goldman, they estimate $44 billion.

Either way, that's an astonishing 20-fold increase over the next decade. Jenny Chang, Portfolio Manager at Goldman Sachs Asset Management hails anti-obesity drugs as "one of the biggest drug classes to be created" — an explosion due to the enormity of the potential market (no pun intended) and the high prices new solutions are commanding.

Those high costs seem not to have dampened enthusiasm or interest.

"There will always be someone," muses Nnaemeka "willing to pay $1,000 to lose just 1 lb... Heck, you could find someone who'd pay $10,000 if you let them. But America, and indeed the world, has severely lost its way if good health is now a status symbol."

Or perhaps, health — or at least thinness — is indeed a new status symbol?

Three days before this piece went out, a significant changing of the guard took place: Novo Nordisk, a diabetes drugmaker from the suburbs of Copenhagen, became the most valuable company in Europe.

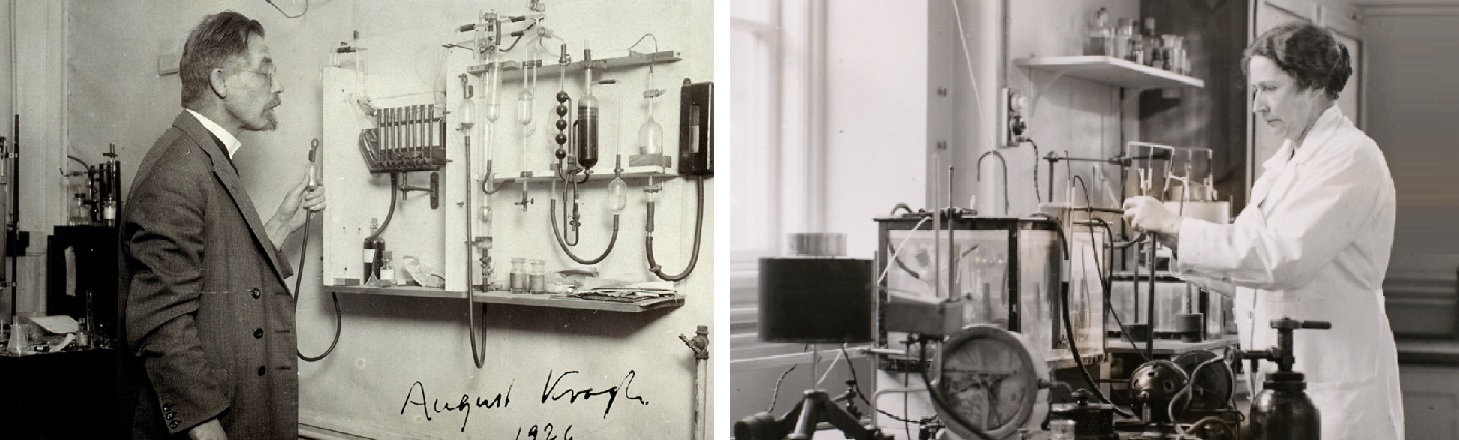

Dr. Marie Krogh and Dr. August Krogh, the married Danish couple who started Novo Nordisk back in 1923

Founded 100 years ago by 2 Danish doctors — Dr. Marie Krogh, the 4th woman in Denmark's history to receive a medical degree, and her husband Dr. August Krogh, a winner of the Nobel Prize in Medicine — the company focused on insulin and insulin products.

Dr. Marie, having developed diabetes, enlisted her husband to help her study her own disease (and hopefully) treat diabetes for herself and milllions of others. Which Novo Nordisk has done with little fanfare for a century... that is, until it released Ozempic and was thrust into shock celebrity.

In the summer of 2023, Denmark's Novo Nordisk took the #1 spot from uber-chic, Paris-headquartered, LVMH, the brainchild of Bernard Arnault — a piano-playing, art-loving, philanthropic Frenchman, nicknamed the "wolf in cashmere."

In under 40 years, Arnault turned his family's engineering firm into the leather goods-haute couture-fine wine-fragrances-and-jewelry juggernaut we all know; vaulting his father's company from the struggling industrial town of Roubaix, at the very edge of France, on the border of Belgium, to a glittering powerhouse at the center of the world of luxury — and heck, the center of the world tout court.

[To our shock, despite its rich history, and despite being the birthplace of Monsieur Arnault, the world's wealthiest man, Roubaix is one of France's poorest towns, with 43% of residents living below the poverty level. It takes a bit of shine off of things to read such dispiriting numbers...]

The Kroghs, founders of Novo Nordisk, atop Bernard Arnault, Captain of LVMH

Valuations, as anyone who watches the markets can attest, swing wildly.

Novo Nordisk is top of the heap this week; next week LVMH may reclaim the title. Prima facie, the 2 companies, Novo Nordisk and LVMH, couldn't be more different.

But let the record show that, in the summer of this year, a Scandinavian maker of insulin products bested a French purveyor of luxury goods by selling a polarizing, super-expensive, much-hyped product that all the celebrities want and that regular folks can barely get their hands on due to limited supply, resulting in desperate buyers turning to underground markets to procure duplicate versions.

Now, where could Novo Nordisk have learned such a thing???

Where could [they] have learned such a thing?"

Wall Street and investors worldwide could be seeing the similarities too.

Are investors perceiving drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy as (soon-to-be-subsidized) commodities with a billion-person user base?

or are they seeing them as (inaccessibly) high-priced luxuries with a million-person clientele?

Illustration: Are diabetes drugs a new luxury? CZ. Nnaemeka

It is ironic — some would say, loathsome — that a drug intended for 'the masses' (literally) is being bought up by 'the classes': the wealthy and well-connected who can afford these expensive new injections.

We called these drugs "Gucci-goods" in our intro — a reflection of the reality that these medications are perceived as much as luxury items as they are as health aids.

The celebrities (mis)using the drug couldn't be farther from the intended population. Which, let's recall, is not even the overweight, but the diabetic.

There's a strange solace, though, Nnaemeka says, in Hollywood's adoption of these drugs.

Why?

Because the stars are performing a vital scientific service for humanity:

"Between the high cost and the global shortages, these new GLP-1 drugs are notoriously hard to obtain. Those in elite circles seem to be getting their hands on the product, nevertheless. And they'll let us know the outcome of their trials — eventually.

As with plastic surgery, "vampire facials," and Botox, the rich, the famous, and the Kardashians are doing the beta-testing for the rest of us who can't afford the treatment (or can afford it, but can't get it).

Hollywood's vanity is actually a service to health science."

Only time will tell what these drugs accomplish.

And only time can tell whether these drugs — in the end — will be a net positive, a net negative, or a net neutral.

In the meantime, we wait.

Nnaemeka agrees with Mark Purcell, lead author of Morgan Stanley’s research report, that obesity drugs are a huge market, but she thinks the current business model needs to be seriously rethought:

“A friend once joked that you can’t get a person to marry you if you can’t even get them to have coffee with you. Similarly, the pharmaceutical industry may be proposing marriage too hastily, with a partner they've never even sat down to coffee with."

Pharma execs, to their credit, have been completely candid about the fact that patients regain weight as soon as they stop their injections. And, because of this weight regain, the industry envisions millions – if not billions – of patients committed to their products forever: using these drugs to lose weight and to keep it off.

But that's a lifelong commitment that is in no way guaranteed.

• The high costs and safety concerns are making new patients hesitant to even try out the drug.

• The shortages are curtailing the progress of existing patients.

• The price tag is putting health carriers off.

In an Atlantic article about the promise and perils of drugs like Ozempic, American writer Derek Thompson — one of the magazine's most captivating thinkers — tabulates a stratospheric figure for the reader (a figure which aligns with our math).

You can't get a patient for life, if you can't even get them (or their insurers) for a month or a year."

If every obese American, Thompson calculates, were to take a semaglutide medication lke Ozempic or Wegovy, for just 1 year, at the current price being charged, the total cost would amount to $2.1 trillion.

For just 1 year.

For a drug that's supposed to be taken forever.

That's 1 hell of a marriage bill — even for 18billionaires.

The brilliant Derek Thompson computes a jaw-dropping figure in his piece for The Atlantic

As Nnaemeka sees it:

"The happily ever after that Big Pharma envisions may be premature. Even if drugmakers pursued only a fraction of America's consumers, who's going to put up the cash for the billions that the medication will cost on a yearly basis?

Someone has to buy a drug for a patient to try it.

Patients need to try a drug, before they will commit to it.

If they can stomach the drug – literally – and handle any side effects, they might stay with it for life.

But you can’t get a patient to stay with you for life, if you can’t even get them (or their insurers) to try you out for a month (or a year).

As a point of comparison, consider the fact that the United Kingdom has an overweight and obese population that is 5 times smaller than that of the US. In the UK, The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence will cover the drug, but only for the obese, and only for a 2-year period.